Interview with Andreas Reichinger, Senior Research Engineer at VRVis Center for Virtual Reality and Visualization Research GmbH, Austria's leading research institution for application-oriented research in the field of visual computing

Museum Guide: We're standing here in your research office. Before us are a series of reliefs of varying scale and quality, which can be used to illustrate your research. Can you describe the complex development process behind them?

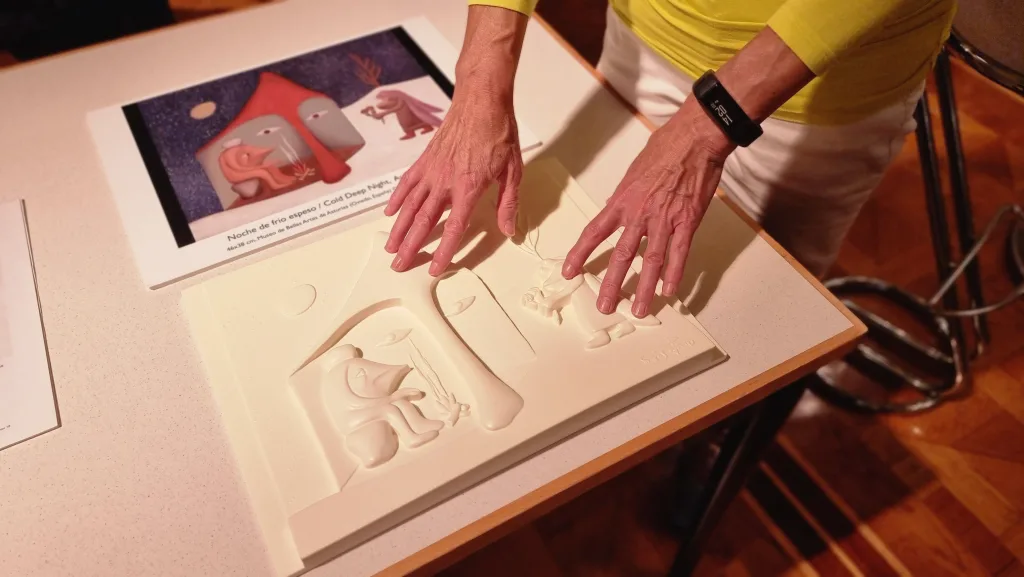

Andreas Reichinger: In 2010, on behalf of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, we began exploring the transformation of artworks into tactile forms to facilitate access to art for people with visual impairments. The status quo at the time was swell prints, where a tactile sensation was created on special paper by heating. Braille printers were also used. These were very simple and inexpensive tools, but they were far from capable of conveying the many dimensions of a work of art.

We initially addressed the question of how to recreate the sense of depth that artists create in their paintings in a printed relief image. Using Raphael's "Madonna in the Green," I then wrote software that allows you to segment individual areas of a painting and assign them different levels of depth. This is not trivial, because if you look at, for example, the arms of the Madonna as she embraces the child, you have to consider several levels and transitions here alone. The three-dimensionality created in the original through light and dark effects, as well as patterns and shading, are extracted in the program using filters that mimic the perception of the human eye and are applied as surface variations in the relief. Important areas such as faces, bodies, and geometric objects are digitally remodeled and integrated into the overall image.

Museum Guide: What process and material is used to create the relief?

Andreas Reichinger: The depth image created on the computer is produced using a computer-controlled CNC milling machine. This has the advantage over 3D printers of delivering higher-quality results, and I have free choice of materials. This is especially important these days due to hygiene and disinfection requirements. Furthermore, milling of this quality and size is still cheaper and faster. Upon request, we can also create a negative impression in silicone, which can then be cast in plastic and reproduced many times, which is very popular for group tours.

Museum Guide: What is innovative about your research, what distinguishes your relief images from manually crafted reliefs?

Andreas Reichinger: The inspiration for our relief images comes from sculpture. For example, from the tradition of the Italian "Museo Tattile," where paintings or architectural models are reproduced for blind people. A British artist recreates relief images from clay, others carve them from soapstone. Craftsmanship and personal interpretation then determine the outcome and quality. Computers, on the other hand, enable precise reproduction and reproducible results that can also be corrected at any time.

Museum Guide: What is the added value of these reliefs for the museum?

Andreas Reichinger: The added value goes far beyond the educational work for people with visual impairments. From the very beginning, my goal was to be able to create relief images on the computer that would be interesting and informative for everyone, not just those with visual impairments. When the relief of Raphael's Madonna was first exhibited at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, right next to the original painting, almost all visitors approached the relief with interest and spent longer than usual contemplating the painting. The relief enables a different, additional approach to the work of art; it opens up new perspectives.

Museum Guide: How long does it take to develop a relief?

Andreas Reichinger: Every picture presents us with its own new challenges, and the development time can vary accordingly. In this respect, each relief is created by hand, albeit on the computer. For the very first relief, the Raphael relief, we are talking months; it was done as part of a research project. At the moment we are at 1 to 2 weeks. First I write a "treatment" - how I see the picture, and how the client sees it. This requires in-depth analysis and often discussions. Because the description of the picture has a huge influence on the quality of the result. Then I give the description to blind test subjects. Based on the feedback, a first rough draft is created on the computer, followed by the detailed draft. The final milling takes between 12 and 24 hours.

Museum Guide: You now produce for many museums.

Andreas Reichinger: We are a frequent partner in EU research projects, but also work directly with art and cultural institutions. Our reference museums include the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Technisches Museum, the Belvedere, the Dommuseum Wien, and the Graz Museum Schlossberg. Our reliefs are also exhibited throughout Europe, for example, at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, the Wallace Collection, the Museo Lazaro Galdiano, the Berlinische Galerie, and the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte in Regensburg.

Museum Guide: What is the feedback from visitors?

Andreas Reichinger: One encounter that particularly touched me was a woman who thanked us with tears in her eyes. She had always been an art lover before she became blind and thought the door to art was now closed for her. Through our work, this door has reopened. We have received several awards for our research contribution to greater inclusion and our inclusive art solutions, including the Heritage in Motion Award 2020 and the WSA Austria Award 2020.

Museum Guide: What is the next step, the next development?

Andreas Reichinger: Another research area is tactile photography, where we offer workshops where visually impaired people not only take their own photographs but also create relief prints, including using a new type of relief printer. Our main focus, however, is on new communication channels, particularly in the spirit of "Design for All": In a three-year EU-funded research project, we developed a tactile, interactive multimedia guide that not only serves people with visual impairments but also takes a wide variety of needs into account. On a screen with a built-in camera that detects the touch of a relief, users can choose between a variety of information channels and perception options: projections and animations in color, representations as sounds, audio explanations, descriptions in sign language and easy-to-read text, background information, and much more – in other words, a guide for everyone, even people without disabilities. That's important to me! Everyone's needs can and should be taken into account. The focus is not on the type of disability, but on the different needs.

Contact: VRVis Center for Virtual Reality and Visualization Research GmbH Donau-City-Str. 11, 1220 Vienna office@vrvis.at +43 (1) 908 98 92