The transformative power of art

The World Health Organization (WHO), based in Geneva, runs a program called "Art & Health" that looks at the positive effects of art on our mental, physical and social well-being. The head of the program is Christopher Bailey, whose career originally began as an actor before moving into research. He and his team are finding more and more scientific evidence and examples of how participation in art and culture gives people orientation, strengthens their ability to act, increases their well-being and increases their self-esteem. Bailey knows from his own experience what he is talking about.

When he lost more than 95% of his sight due to glaucoma not so long ago, it was more than just a physical loss. He felt emotionally exiled from the world. He did manage to create an alternative spatial world around him, but it was only his engagement with art that gave him a new, meaningful attitude to life.

One day, the Museum of Modern Art in New York invited him to take part in a podcast series about the impact of art. He was supposed to talk about Claude Monet's painting "Water Lilies". He was skeptical at first, but then accepted the challenge. To his astonishment, when he looked at the painting, he realized that Monet actually painted the way he, Christopher Bailey, saw through the glaucoma veil, and that the way he saw the world could be perceived as beautiful.

"When I look at the water lilies, I experience a feeling of completeness. Surface, depth and reflection merge together, just as past, future and the present moment become one. I have realized that I have lost nothing. I feel no anxiety or fear. I simply revel in the joy of color and celebrate the present moment. For me, that is the healing power of art."

The right to art and culture

During the Corona pandemic, the closure of cultural institutions has made us all experience what we are missing when we cannot enjoy art and culture, when we do not have access to it: we feel a lack of inspiration, creativity, joy, happiness and hope. We become anxious, insecure, hopeless and even depressed.

Art and culture are essential pillars of social development and cultural participation is a fundamental part of the human experience. That is why access to art and culture is so important for all people, and why no one should be excluded. This principle can already be found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948: "Everyone has the right to participate freely in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits." In reality, however, equal participation is made more difficult for people with disabilities. They are confronted with physical barriers and experience social, intellectual or communication limitations that make it difficult for them to access content and information.

Accessibility and inclusion in the museum

The unrestricted and equal access to art and culture is described with the terms “accessibility” and “inclusion”.

Accessibility means the extensive removal or avoidance of barriers, be they physical, mental, social or intercultural. Inclusion goes a step further and means participation for all people, regardless of gender, age, origin, religion, education or individual impairments. The legal basis for this was created in Austria with the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008 and with the Federal Disability Equality Act of 2006, which has been fully in force since 2016 after a ten-year transition period.

The catalogue of requirements for museums is clearly growing, because the institution as a whole must be thought of inclusively.

Nils Woebke,

Head of Lebenshilfewerk Hagenow, capito Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Being a barrier-free and inclusive museum affects many areas and tasks of museum work, from structural accessibility to exhibition design and service offerings to communication and mediation. In addition, there are the different needs depending on the type of disability, which should be considered as interconnected and interlinked as possible.

- For people with reduced mobility, for example, it is about barrier-free access using ramps and lifts, appropriate passage widths and handle heights, smooth subfloors, wheelchair access under desks and display cases, disabled parking spaces and disabled toilets.

- Hearing-impaired people need a visual representation of information, for example in sign language, or inductive hearing systems.

- For people with visual impairments, orientation aids that use strong contrasts and tactile aids should be provided, as well as other forms of description and communication that include not only facts but also moods.

- In cases of intellectual barriers and learning disabilities, information and texts in so-called easy language are helpful; that is, short and simple, without compound nouns and without foreign words.

Implementing the various inclusive measures and offers requires resources and expertise that are not a given and can often only be created step by step. But if inclusive approaches and accessibility are consistently considered and planned for in all activities from the outset, they do not necessarily have to be more expensive or difficult, says Jennie Schellenbacher, art mediator at the Vienna Museum and founding member of the ARGE Inclusive Museum. "We have observed that although a lot is happening in the area of inclusion in the museum landscape, this has also resulted in a lot of 'island knowledge' and that everyone is facing similar challenges. We wanted to give people the opportunity to exchange ideas about projects with colleagues from other museums, to discuss new findings and to share concrete practical experience reports with each other."

It should be a matter of course for all of us to involve people with disabilities in inclusive programs from the outset, because they also live self-determined lives and make decisions in their lives every day, so why not also when dealing with art.

Rotraut Krall,

former head of art education at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Nothing about us without us

When Rotraut Krall, most recently head of art education at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and a proven expert in the field of inclusion, set up her program, she got support from a blind person. The aim was to describe art objects in a lively, empathetic way. This is not always easy for art educators, who mostly have an art history education, because you have to proceed very differently than you learned in your studies or in an academic professional environment. "I still remember our first visit to the museum together, where we chose an object for a tactile relief. I described a few pictures and noticed from her reactions what she was missing, what she needed so that she could imagine something. Then you have to do it again and again; practice pays off." The way of developing inclusive mediation offers together with the target group is a relatively new, innovative approach. It makes it possible to develop a mutual understanding of the different perception possibilities and needs. Mediation offers that are offered not only for but also by people with disabilities go a step further.

"Inclusion in museums has been an issue for a long time, but always with the expertise of the existing mediators. Our concept is to employ people with disabilities as art mediators, thus giving them a new role. People with disabilities are permanently employed in the museum. Through these daily encounters, the awareness in the institution changes," says Nils Wöbke, director of capito Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

The interesting thing is that offers from people with disabilities are particularly well received by people without disabilities. The way in which they access art creates new perspectives, not least because the communication is less fact-oriented and allows room for emotions.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum has expanded its participatory approach as part of an EU research project and brought together several types of disabilities into a development team. Project manager Rotraut Krall: "Thanks to this approach, we were able to get much closer to the real needs that every person with a disability has, and also to the variety of needs that we were previously unaware of. We have grown much more deeply into the feelings of other people; we would not have been able to experience this without their support."

Self-determined enjoyment of art through new technologies

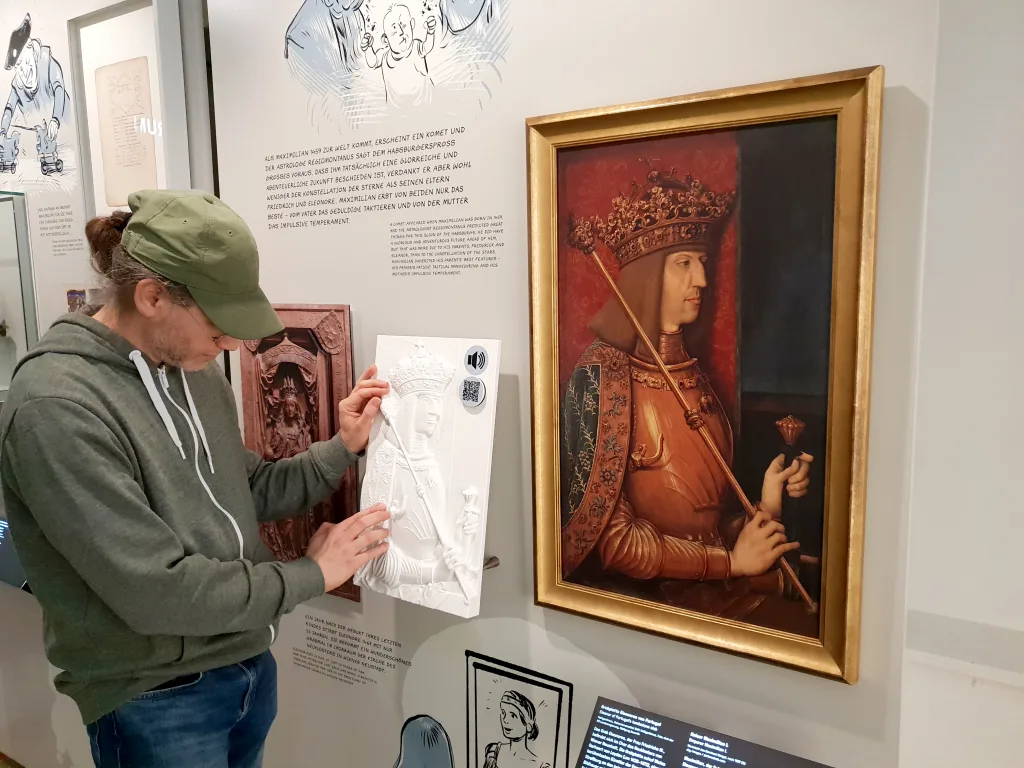

A range of technological tools supports inclusive mediation work and enables self-determined access to art and culture, independent of mediation by trained staff. For example, hand-crafted tactile reliefs have long been in use to recreate exhibition objects that can be touched. An Austrian research institution, the VRVis Center for Virtual Reality and Visualization, is leading the development of the latest computer-generated reliefs.

Compared to hand-crafted reliefs, the computer enables precise reproduction and reproducible results. In the case of paintings, which are a particular challenge, the image information is translated into a figurative, three-dimensional impression that makes all levels of depth perception, such as those created by the brain when seeing, tangible. Originally designed for people with visual impairments, all visitors can benefit from tactile perception, especially children or people with cognitive impairments.

In the spirit of a holistic approach, VRVis is constantly working on the further development of tactile communication methods, such as an interactive multimedia guide that takes a wide range of needs into account. Here you can choose between a variety of information channels and perception options: animations in color, representations as sounds, audio explanations, descriptions in sign language and in easy language, background information and much more.

Digitalization now supports a variety of technological tools in the area of accessibility and inclusion. Another innovative example is the capito app. The app can provide texts in different language levels at the same time. This makes reading with comprehension possible for a wide range of target groups. This is a broad field of activity, because according to current studies, around half of the population does not understand the language used by authorities, companies and institutions.

Accessibility is a basic requirement for equal participation of all people in daily life and for an inclusive society. Today, museums must also ensure extensive accessibility: starting with access to the building through to the presentation of the exhibits.

Rudolf Kravanja,

President ÖZIV Federal Association

The capito app is based on GER, the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. GER distinguishes between several language levels, from short, simple sentences (language level A1), to language for building knowledge (language level A2) or colloquial language (language level B1) to technical language (language level C2). Museums and cultural institutions usually communicate at language level C2. With the capito app, complex texts can be read or read aloud at up to four levels using a QR code, and you can switch between levels.

The right language level depends not only on reading skills, but also on the visitors' previous knowledge, previous experience and personal interests. Museums buy a basic license, and visitors can use it free of charge, either via a web link or a QR code.

"The capito app is a cost-effective all-round solution. The classic audio guide is no longer necessary, visitors have the app in their pocket in the form of their smartphone. Visiting the museum is barrier-free and easy to understand, and the museum also receives valuable visitor data that helps to optimize the museum visit and the exhibition design." (Walburga Fröhlich, Managing Director of capito App)

Inclusive design offers comprehensive solutions for all

With her design office prenn_punkt, designer Doris Prenn has placed a focus on inclusive exhibition design, which she sees as a comprehensive design process that leads to results that can be used by as many people as possible, even if different requirements must be taken into account for each target group.

The Charlotte Taitl House learning and memorial site is a good example of their comprehensive approach. Already in the access area, a white, multi-sensory floor information system guides visitors to the entrance. Larger-than-life black metal panels with lasered and tactile birth and death dates of the victims lead visitors to the exhibition.

A tactile plan in the entrance area provides orientation for blind and visually impaired people. In the memorial room itself, the names of the victims are inscribed in white spot varnish along the walls, complemented by a surrounding Braille band that serves as an information carrier and offers additional orientation in the room. The dates and life stories of the victims are told on steles, which are distributed in the room in a clear order.

Selected photos and documents are tactile. More detailed information can be accessed via touchscreens, and there is also a workstation with a PC, Braille display and Internet access. All information is translated into audio description and sign language. The museum won the complemento 2018 from the ÖZIV Federal Association for People with Disabilities and was included in the honorary list of the 2018 Inclusion Prize from Lebenshilfe Austria.

by Doris Rothauer